from: adelaidescreenwriter.blogspot.com.au

Diane Drake is a screenwriter based in Los Angeles. She is best known for writing Only You (1994) and What Women Want (2000), and also teaches screenwriting at the UCLA Extension Writers’ program.

Diane Drake is a screenwriter based in Los Angeles. She is best known for writing Only You (1994) and What Women Want (2000), and also teaches screenwriting at the UCLA Extension Writers’ program.

I first came across her name a few years ago when a friend sent me a copy of her UCLA screenwriting Course Outline that he’d found online. I read it and immediately wanted to do that course, but couldn’t afford the travel costs. Years later, when I got the chance to ask her a few questions, I jumped at the opportunity.

* Where were you born, and grow up?

I was born and grew up in Los Angeles—the San Fernando Valley, to be specific, but will confess I have done my best to lose the accent. I think I may have succeeded as I was recently traveling in New Zealand and Australia, (which I loved, btw), and was told I sounded Canadian, so—mission accomplished.

My parents were musicians, (mom was a singer and dad was a saxophone player), and my brother was a professional drummer for a long time. Alas, I didn’t inherit the musical gene, so I had to go another way.

* What school did you go to?

I went to the University of California, San Diego. My plan was to study either Marine Biology or Communications/Visual Arts. Once I got there, I found out the Marine Biology program was for grad students only—hence, Communications/Visual Arts.

* When did you first take an interest in films/stories?

* When did you first take an interest in films/stories?

Like most everybody, I had some interest in films and stories growing up. As a kid, I specifically remember watching and being fascinated by the film Hud and also Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, (hm, perhaps I had more of an interest in Paul Newman?) But I didn’t, and honestly still don’t, have the great penchant for old movies that many of my peers did and do. I was generally more interested in being active, out doing things rather than being inside watching movies.

After graduating from college, though, I suddenly became interested in literature. I graduated and didn’t know what to do with my Communications degree, so like a lot of people at the time, for lack of anything better to do, and in an effort to be “practical,” I went to graduate school to get an MBA. I managed one torturous semester. I remember I had an epiphany one day in my accounting class when it suddenly struck me that not only did I hate this, but that if I somehow stuck with it, my degree would qualify me to do it for the rest of my life. That was that. I quit grad school, (and spent years paying off just one semester’s worth of loans), but it was definitely the right decision.

The other thing that happened while I was ostensibly getting my MBA, and trying to avoid any and all classwork associated with it, was that I decided I needed to know more about classic literature and art. When people referred to For Whom the Bell Tolls, or The Grapes of Wrath, or any number of other classic novels I’d missed in school, I felt ignorant and wanted to know what they were talking about.

The other thing that happened while I was ostensibly getting my MBA, and trying to avoid any and all classwork associated with it, was that I decided I needed to know more about classic literature and art. When people referred to For Whom the Bell Tolls, or The Grapes of Wrath, or any number of other classic novels I’d missed in school, I felt ignorant and wanted to know what they were talking about.

After I quit grad school, I got a job working as a secretary for the Warner Cable Company. At the same time, I enrolled in a night class in Art History, and started my own sort of self- directed “course” in the classics, reading maybe a hundred or so of the books you always hear about—Dickens, Tolstoy, Austen, Melville, Hemingway, etc., etc. It was incredibly eye-opening for me, richly rewarding, and I think ultimately proved quite valuable.

* What was your first paying job?

While I was still in high school, I sold hot dogs at Magic Mountain, (an amusement park). I worked in the “Mini-Bar” and while the job had its drawbacks– I still shudder at the vivid memory of cleaning the grill– the man who hired me suggested that particular job because the other girls working there happened to be really funny and fun. He was right. I wish I knew where they are now, a couple of them were truly hilarious. Maybe one is now Tina Fey?

* What was your first job in the movie business?

Technically, it wasn’t really the movie business, but close enough. While I was in grad school the only thing that really interested me was a report I’d done on the Warner Co., which at the time also owned Ralph Lauren and a number of other brands, including what was then called “Warner/Amex Cable” which had MTV, Nickelodeon and The Movie Channel. I thought the company sounded interesting, so I sent them a letter expressing my interest in working for them. A woman in marketing was looking for a secretary and I got the job. It wasn’t a studio, but the building was basically on the Universal Studios lot, we could eat at the commissary, etc., and got me that much closer to the business. Not long thereafter my boss was fired and I was fired, (this was to happen to me a number of times—it’s showbiz), but it was a start.

* How did you get to be a Vice President of Creative Affairs for Sydney Pollack?

After the Warner Cable job, I managed to get a job as an assistant in the Legal department at Columbia Pictures. It was my first job actually on a studio lot, and it was while working there that I discovered there existed such a job as a “reader,” people who were paid to read scripts all day long. Also, on that job I met a number of other people working as secretaries, one of whom a few years later went on to work for Sydney Pollack.

Anyway, this reader position sounded like a dream job to me at the time, and while I wasn’t able to land that job at Columbia, after a stint working for a producer at Fox, I managed to get a job as a reader/assistant to a Vice President working at an independent production and financing company called Producers Sales Organization (PSO). Not too long thereafter, my boss was fired, but this time I was promoted. Thus, I had my first executive job as Acquisitions Director, until someone else was brought in above me, and I was fired again.

Only You: And the slipper fits…

After that, I read scripts for a number of different companies and producers including PBS/American Playhouse. It paid little, but it was great training, both in terms of what to do and what not to do. And then one day I got a call from a friend of the friend I’d mentioned earlier from Columbia Pictures, who’d gone on to work for Sydney, telling me she’d heard he was looking for a story editor. This, to me, was the dream job of all dream jobs.

I had to do sample coverage, (an evaluation like a book report), on five or so scripts, and later heard that Sydney had picked out three candidates from those samples, and I was one of the three. My friend who was then his secretary had not yet told him she knew me, but at that point I believe she did. Anyway, I wound up being hired by the president of his company at that time, a great guy named Mark Rosenberg. I was truly the happiest girl in the world to get that job. It was an extraordinary experience. Later, I was promoted to Vice President of Creative Affairs.

* What did you learn from working with Sydney Pollack?

* What did you learn from working with Sydney Pollack?

I learned so much from Sydney and truly don’t think I’d have ever been able to succeed as a writer without that experience. He was such an incredibly intelligent, talented and driven man. He was a perfectionist and had an amazing work ethic, and was pretty much always the smartest guy in the room. He was also, as you might imagine, extremely demanding and intense. The job was a challenge, but most of the time in a terrific and exciting way.

* You’ve had an unusual career in that you were a movie executive before you took up writing. Most people go the other way. What impelled you to take on the precarious life of a writer?

I guess I was feeling burned out on reading other people’s material at the time and feeling like, if I knew so much, why didn’t I put my money where my mouth was? The job of a creative executive and the hours involved can be quite grueling. And I’d look around at some of the writers who were working on projects for Sydney, and this one was off on a cruise to South America, and another was on location with a film in France—it just seemed like a much more free and potentially rewarding life. Plus, this was back in the heyday of spec scripts selling for boatloads of money, and Sydney—great a guy as he was—was, shall we say, “frugal.” Despite my title, I really wasn’t making much money there, and was kind of struggling, so having already spent quite a number of years analyzing material, I figured I owed myself a shot at creating my own.

That said, let me just state the obvious—it’s a heck of a lot easier to sit on the sidelines and “critique” the work of others than it is to face the blank page yourself. A LOT easier.

Only You: You’re going to let a few little letters keep us apart?

* What was your first spec script about?

It was called Dog Meets Cat—about a dog and a cat who are forced to live together and don’t want to. It didn’t sell, but it did get me an agent and a small assignment job to write a treatment, which got me into the Writers Guild. So, looking back, that little script, written in a few months time, at night, when I was still working for Sydney, served me quite well.

* That script was never produced, but it helped you get a writing assignment from Hanna-Barbera. What came out of your time with them?

Not a lot in terms of a movie. It was an assignment to adapt The Prince and the Pauper with dogs. I don’t think the project was ever made, but for me it was a great deal in that it got me into the writers guild, got me health insurance, and, as it paid $25,000, it bought me the time to write my second script, Only You.

* Only You was the first script you sold. How did the success of that movie change your life and career?

Basically, it gave me a career (and a lot of money). I went from being a struggling writer, a few thousand dollars in debt, to having a career. It was an extraordinary, almost out-of-body, experience. After my agent and lawyer told me the news that they’d closed the deal for $1 million, I remember waking up the following morning and walking in something of a daze to the local 7/11 to buy the trade papers, wondering if it had actually happened. And there it was, in black and white, on the front cover of The Hollywood Reporter and Daily Variety, and I remember thinking to myself two things: First, “Thank goodness I hadn’t just dreamed it all,” and second, “Well, they’re going to have to pay me now. Now that it’s been printed in the paper.”

Only You: Mr Wright, in his socks…

* You worked with the director, Norman Jewison, on “Only You” for about six months before filming. What did you learn from him?

Norman is so lovely, and smart, and funny—he’s a real charmer, and it was a joy and a thrill to work with him. He did kind of trick me, though, I realized after the fact. The way we’d work was I’d go to his office, trusty copy of my script in hand. And he’d sit at his desk and read aloud from his copy. If he didn’t like the way a scene was working, (I later realized), he’d read it badly. He, like Sydney Pollack, started as an actor. A lot of what was in the original script was a little silly and slapstick-y and I think he wanted to minimize those elements, so he would read those scenes badly, and I’d think, “Oh good God, yes, we MUST get rid of that.”

Diane Drake at Franco Zefferelli‘s villa. 1993.

Ultimately, though, I do think a little of the breeziness—a tonal thing that told you the whole thing was supposed to be a lark—somehow got a bit lost along the way. Perhaps more owing to the way Marisa Tomei chose to play it, which was a bit more “dramatic” than what I’d imagined. Not unusual, I’m afraid, from script to screen, for things to change substantially, and the original writer to not have much say about it. Still, it was an extraordinary experience, and I want to add that Robert Downey Jr. is not only one of the most brilliantly talented, but also one of the most gracious and kind people I’ve ever met in Hollywood. He is simply lovely.

* Only You could have been set anywhere. Why was it set mostly in Italy?

I knew by virtue of the nature of the story that it had to go somewhere. It, she, had to literally take off. And I wasn’t interested in going from, say, L.A. to New York. I’d been to Italy for the first time a few years earlier, had fallen in love with it, and wanted to return, so when I asked myself where I wanted to go, that was the obvious answer. Plus, it’s just by nature such a romantic and beautiful place, and it hadn’t been done to death at that point. The only time we’d recently seen a romanticized Italy on the big screen was in more art-house indie fare like Enchanted April or Cinema Paradiso. (This was pre-Under the Tuscan Sun, etc.)

Positano. Photo taken by Diane Drake in 1993, during filming of ‘Only You.’

At the time a good writer friend of mine, whose advice I highly respected, said to me, “It’s a good script, but don’t set it in Italy.” When I asked him why not, he said, “Because if you set it in Italy, it becomes a movie about Italy.” As much as I trusted him and his opinions, I knew he was wrong about that, and thank goodness I didn’t listen and stuck to my original plan, as not only did I get a great trip to Italy out of it, but I’m convinced that the setting contributed to the movie’s success and longevity in DVD. Turns out a lot of people like taking a vicarious trip to Italy as much as I did.

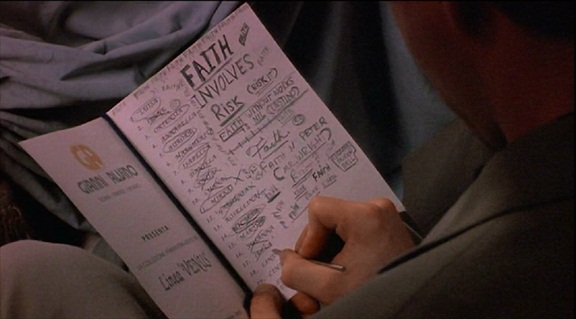

* The theme of Only You is stated explicitly in writing. “Faith involves risk.” Both the woman Faith, and faith that your choices are right (Wright) for you. Do you recommend that approach to theme for new writers?

Only You: Faith involves risk, and You make your own destiny.

Actually, not to be contrary, but to me the theme is more what the fortune teller tells Faith in a moment of conscience, “The truth is, you make your own destiny. Don’t wait for it to come to you.” I think that’s something I was wrestling with at the time, working for Sydney, but feeling like I wanted to do more, and knowing it was up to me to take the risk and do it.

* What Women Want was an enormously successful movie. It was your idea, but other people took writing credit on that film. What happened there?

What Women Want: Thanks for all your great ideas…

Let’s just say—it’s complicated. The movie was based on my original idea and my original spec screenplay which predated the involvement of anyone else. I like to work with ideas which I consider universal fantasies, and when I came up with that one, I knew I’d hit on something special. Little did I know how ironic it would ultimately be that I created a story about a character who steals and takes credit for someone else’s ideas. As far as the final credits are concerned, I felt the Writers Guild arbitration was mishandled abominably, but I know I’m not the first writer to feel this way, and sadly I’m sure I won’t be the last. On the plus side, my name is on the film, it was a huge success, and I got paid handsomely. Glass half full.

Did I learn any lessons? I always advise any writer to register his or her material both with the Guild and (in the US) with the US Office of Copyright. It won’t keep people from stealing from you, but at least you’ll hopefully have some recourse if it happens.

On a related note, the movie was recently remade in China with Chinese stars, and I received a nice check in connection with that. Just goes to show you the power of a good idea and good script.

What we all want: A happy ending

* You’ve been teaching at the UCLA Extension Writers’ Program since 2009. What one main idea do you try to impress on students?

I place a great deal of emphasis on structure. Movies have a specific structure that is often invisible to those who are not versed in it. And they’re almost always about one main character, even “buddy movies” have a character who is more the lead than the other.

Another thing I try to make my students aware of is what makes a movie. “Movies are about the moment where somebody’s life changed.” That’s a quote from Christopher Walken, and it’s one of the best I’ve ever come across in terms of summing up what a movie is, and isn’t.

Beginning writers all too often get caught up in what they think is interesting dialogue or a dramatic moment, and forget to keep their eye on the big picture (forgive the pun).

* Nora Ephron says she became a director in order to protect her scripts. Have you ever thought of becoming a producer/director?

No, it’s a whole different ballgame, and unfortunately, not one I think I’m particularly suited to.

* You have your own script consultation business. What prompted you to do that?

Yes, I do consultation through my website, www.dianedrake.com. I really love doing it. I feel I’m able to bring a lot of experience and expertise to the table, both as an executive and as a produced writer. My clients have been so sweet and appreciative, and it’s been gratifying. Writing is so personal to people, and I feel quite honored to be let in on, and able to assist with their pursuit of their dreams.

* Have you ever run into sexism/ageism in Hollywood? How did you handle it?

I think it certainly exists and basically I try to just ignore it and go on about my business, to not give it any more power. Obviously, there’s no question that there are plenty of weasels in Hollywood, but there are some really great and smart and genuine people, too (for example, Sydney Pollack). I like to believe that, in the end, talent is what matters most. That, and persistence. And luck certainly doesn’t hurt either.

* Are you working on a screenwriting advice book?

I am. Stay tuned.*

* What one book would you recommend to a young wannabe screenwriter in Adelaide?

This is not a screenwriting book, per se, but a book about writing and the creative life in general. Becoming a Writer by Dorothea Brande. Written in 1934, but with so much contemporary resonance and wisdom. Full of timeless, wonderful insights and advice about writing from the heart, and the joys and perils of life as a writer. Just one example: she talks about seeing things freshly, or cultivating what she calls, “The innocent eye.” She advises, “Try to be one of those people on whom nothing is lost.” I think she’s something of an antecedent for Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way.

If people are looking for a book on the nuts and bolts (and trials and tribulations) of screenwriting, there are a ton of them out there, but none I really love. (I must finish mine!) But for the time being, I think Viki King’s How to Write a Movie in 21 Days, is quite good, even if, as I tell my students, the title is absurd.

UPDATE: Diane’s own book on screenwriting, Get Your Story Straight is newly complete. Click here to order a copy.

UPDATE: Diane’s own book on screenwriting, Get Your Story Straight is newly complete. Click here to order a copy.

* Name ten of your all-time favorite movies.

The Lives of Others (2006)

Local Hero (1983)

Thelma & Louise (1991)

Pulp Fiction (1994)

Roman Holiday (1953)

Bull Durham (1988)

Toy Story (1995)

Swingers (1996)

Man on Wire (2008)

Lost in Translation (2003)